Red-Bull-Serie, fünfter und letzter Teil

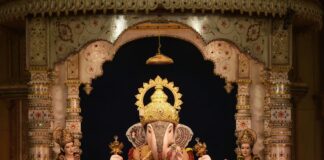

Rodri (Manchester City) und RB-Rekordtransfer Xavi Simons im Zweikampf um den Ball. Beide Klubs sind Paradebeispiele dafür, wie die sogenannte Multi Club Ownership funktioniert.

Quelle: Weinert/RND (Montage), Foto: IMAGO/motivio

Red Bull verändert den Fußball, aber nicht alleine: Klub-Netzwerke prägen die Branche zunehmend – und fordern die Verbände heraus. Über eine Entwicklung, die dabei ist, die bestehende Ordnung im Sport zu sprengen.

In Christoph Breuers Büro hängen Tradition und Moderne nebeneinander an der Wand.

Breuer ist Professor am Institut für Sportökonomie und Sportmanagement der Deutschen Sporthochschule Köln. Sein Büro liegt im Stadtteil Müngersdorf, nur rund zehn Fußminuten vom Stadion des 1. FC Köln entfernt. Der Klub spielt aktuell mal wieder in der zweiten Liga, gehört allerdings zu den großen deutschen Traditionsvereinen, war erster Bundesliga-Meister, Double-Sieger 1978, mobilisiert die Massen auch heute noch mehr als einige Champions-League-Teilnehmer.

In Breuers Büro hängt ein Trikot des 1. FC Köln mit den Unterschriften der Mannschaft, gerahmt und hinter Glas. Daneben ein Trikot von Bayer Leverkusen, ebenfalls im Rahmen, ebenfalls hinter Glas. Der aktuelle Double-Sieger ist Kölns lokaler Rivale, doch der Klub, gegründet als Werksverein des Chemie-Giganten Bayer und ausgenommen von der 50+1-Regel, steht auch für einen anderen Fußball als der 1. FC Köln, für den modernen.

Genau um diesen Gegensatz, Tradition auf der einen Seite, Moderne auf der anderen, geht es auch in der Debatte um das Engagement von Red Bull im Fußball. Der Konzern fordert die klassische Ordnung heraus, nicht nur mit dem Leipziger Emporkömmling Rasenballsport, sondern mit einem Netzwerk an Vereinen auf der ganzen Welt. Red Bull ist eines der prominentesten Beispiele für sogenanntes Multi Club Ownership (MCO), also dafür, dass ein Eigentümer mehrere Vereine besitzt. Das bedeutet: Verschiedene Klubs, die qua Natur des sportlichen Wettbewerbs eigentlich Konkurrenten sind, gehören in solchen MCO-Konstrukten zum gleichen Haus, werden zentral gesteuert und bringen die bewährte Rangordnung im Fußball in Bedrängnis, weil Netzwerk-Klubs Vorteile gegenüber herkömmlichen Vereinen haben. „Wenn die MCOs alle ihre Möglichkeiten ausspielen würden, hätten die klassischen Klubs Schwierigkeiten“, sagt Wissenschaftler Breuer in seinem Büro in Köln.

Wie hart sind die Verhandlungen zwischen RB und RB?

Die Möglichkeiten, die Breuer meint, lassen sich gut durchdeklinieren am Beispiel von Red Bulls Fußball-Imperium: Wie bei vielen MCO-Modellen gibt es auch in diesem Fall eine klare Hierarchie zwischen den Klubs. An der Spitze steht RB Leipzig, vertreten in der Bundesliga und der Champions League, diesem Verein arbeiten die anderen Klubs zu, zum Beispiel mit der Ausbildung von Talenten. Sinnbildlich dafür ist der Umstand, dass seit 2012 schon 20 Spieler von Red Bulls Salzburger Filiale fest nach Leipzig wechselten. In den sozialen Medien wird bei jedem Geschäft zwischen den beiden Vereinen gespottet, dass die Verhandlungen sicher hart gewesen seien.

Mit der Verpflichtung von Jürgen Klopp als Galionsfigur seines Fußball-Imperiums hat Red Bull eine Kampfansage an die Branche ausgesendet. In einer fünfteiligen Serie nimmt das RND unter die Lupe, wie RB im Volkssport Nummer eins zu dem wurde, was es ist – und wie der Konzern den modernen Fußball verändert.

Mit dem Besitz verschiedener Klubs in allen Winkeln der Welt sichert sich Red Bull den Zugang zu verschiedenen lokalen und regionalen Märkten, das gilt für die Rekrutierung und Ausbildung von Talenten genau so wie für Marketing und die Werbung von Fans. Mittlerweile ist Red Bull neben Österreich und Deutschland auch mit Klubs in den USA (New York Red Bulls), Brasilien (RB Bragantino) und Japan (RB Omiya Ardija) vertreten. Im vergangenen Mai kaufte sich der Getränkehersteller auf dem attraktivsten Fußballmarkt der Welt ein, nämlich in England, allerdings nur als Anteilseigner und Trikotsponsor von Leeds United. Der Verein ist eine Art englischer 1. FC Köln: aktuell in der zweiten Liga aktiv, von der Geschichte und dem Fan-Aufkommen aber einer der großen Klubs des Landes. Seit Ende des vergangenen Jahres besitzt Red Bull auch Anteile am französischen Zweitligisten Paris FC.

Nicht nur Leipzig ist ein MCO-Klub

Das zweite bekannte Beispiel für Multi Club Ownership im europäischen Fußball neben Red Bull ist die aus Abu Dhabi gesteuerte City Football Group mit Manchester City an der Spitze. Neben dem englischen Dauermeister und Champions-League-Sieger von 2023 gehören zwölf weitere Klubs auf der ganzen Welt komplett oder teilweise zu dem Konstrukt, nach eigenen Angaben „der weltweit führende private Eigentümer und Betreiber von Fußball-Vereinen“.

Die roten Bullen als Markenzeichen

Was die Klubs von Red Bull und die City Football Group verbindet: Sie haben ihre eigene Identität ganz oder teilweise zugunsten der Identität des übergeordneten Konzerns aufgegeben. Die Vereine aus dem Red-Bull-Imperium spielen überwiegend in weißen Trikots und roten Hosen, die Klubs der City Football Group spielen vornehmlich im Himmelblau von Manchester City. Auch die Klubwappen in den jeweiligen Konstrukten ähneln sich oder sind praktisch identisch. Bei den RB-Vereinen in dieser Hinsicht prägend: die beiden roten Bullen.

Important as a unified brand image is for clubs owned by the same entity, what is even more crucial is the fact that they benefit from the intelligence and resources of the collective. This means that talents can be trained at different locations and then transferred to the top club in the portfolio, knowledge about player development or medical treatment can be shared between the various clubs, and individual departments – such as the PR department or the human resources department – could work for the different clubs in the network, allowing owners to save costs. Within the networks, synergies can be created that give the clubs an advantage over clubs that are traditionally on their own.

Question to sports economist Christoph Breuer from the German Sport University Cologne: Does this mean that the German record champion and industry leader FC Bayern would have problems if RB Leipzig were to fully exploit its advantages through the Red Bull network? “In the medium term, yes. In the medium term, the advantages of distributed talent production and knowledge sharing are compelling,” says Breuer. However, the starting point is always crucial. FC Bayern has built up such large economic advantages over the years that it will be difficult to offset them. That means: FC Bayern will benefit from its past for a long time. But RB Leipzig is catching up.

The way the club does this, Breuer’s team conducted a study that fundamentally deals with the advantages that clubs have in network structures. Based on data from the transfermarkt.de portal, the study examined a large number of player transfers in recent years and found that transfers between clubs with the same owners often take place below market value. This phenomenon was particularly noticeable in transfers within the Red Bull network. According to the study, transfers between the clubs were on average five million euros cheaper than between clubs without a common owner.

Does RB Leipzig receive a discount in deals with the Red Bull branch in Salzburg? Contradiction from Saxony: “That’s not correct,” said managing director Johann Plenge at the beginning of January about the study from the German Sport University: “The moment a transfer takes place below market value, auditors and the tax office would raise their hands immediately – by the way, rightly so – UEFA and the associations anyway.” Transfers below market value would not be possible legally and regulatory, says Plenge.

As decision-makers at RB Leipzig, the 40-year-old executive sits practically at the center of a development that is increasingly shaping world football, namely the trend towards Multi Club Ownership. According to UEFA, the number of clubs organized in such networks increased from 40 to more than 230 worldwide between 2012 and 2023, with Europe’s football association distinguishing between clubs that actually have the same owner and clubs that only receive investments from the same source. In any case, there are economic entanglements between the clubs.

In Germany, RB Leipzig is not the only club whose owners own additional clubs. FC Augsburg, Hertha BSC, and 1. FC Kaiserslautern have also become MCO clubs by selling shares. And FC Bayern has established its own network: Together with the Los Angeles Football Club, the German record champions took over the Uruguayan traditional club Racing Club de Montevideo.

Critics – including fans of FC Bayern – see Multi Club Ownership as the greatest threat to football. Because the network clubs would have financial advantages over independent clubs. Because smaller clubs in the networks would be reduced to mere training grounds for clubs like Manchester City or RB Leipzig. And because there could be agreements if two clubs with the same owner compete in the same competition.

How to understand the UEFA rules?

The UEFA regularly deals with the last of these three issues and is likely to do so more in the future. According to the rules of the European football association, clubs participating in the same competition must be strictly separated from each other to avoid conflicts of interest. However, what “separated” means is a matter of interpretation for UEFA.

An example: In 2017, two clubs from the Red Bull empire, namely the branches from Salzburg and Leipzig, competed in the Champions League for the first time. UEFA came to the conclusion that “the relationship between Red Bull and FC Salzburg only corresponds to a normal sponsorship relationship.” After changes in the structure and management and a separation of the group and the club, “Red Bull does not exert decisive influence on Salzburg”. The UEFA had no objections to the start of the two RB teams in the same competition.

Similar examples from the current season: UEFA allowed Manchester City and Girona FC to participate in the Champions League, even though both clubs (wholly or partly) belong to the City Football Group. Manchester United and OGC Nice were granted the right to participate in the Europa League, even though both clubs belong to different parts of the British chemical giant Ineos. UEFA granted all clubs the right to participate in the respective competitions because it had concluded that the separation between Manchester City and Girona and between Manchester United and Nice was sufficient. Among other things, the City Football Group and Ineos had transferred parts of the smaller clubs (Girona and Nice) to trustees in order not to operate as shareholders themselves.

Uefa does not want to categorically reject the model

UEFA struggles to keep up with the new football world, and it is not entirely clear how serious it is about it. In 2023, for example, UEFA President Alexander Ceferin said in an interview with former Manchester United captain Gary Neville that stricter rules were needed to protect football from damage caused by Multi Club Ownership, on the one hand. On the other hand, this model should not be categorically rejected. The background to this view is likely the money that investors pump into football through owning multiple clubs. And so, the trend towards Multi Club Ownership represents the general discomfort of many observers that football no longer cares about earning money. That money now dominates football.

More examples of this view: the awarding of the 2022 World Cup to Qatar and the 2034 World Cup to Saudi Arabia, the sale of locally rooted traditional clubs (Paris Saint-Germain, Manchester City, Newcastle United) to Gulf states with questionable human rights records (Qatar, Abu Dhabi, Saudi Arabia), or the fact that UEFA expanded the Champions League for this season and FIFA will host a large-scale Club World Cup for the first time this summer, all with the aim of generating more revenue. In this context, Red Bull has built up its football empire since 2005.

Back to Leipzig, to the headquarters of the local Red Bull branch at Cottaweg. For about 50 minutes, club boss Johann Plenge talks in early January about the big and small questions surrounding RB Leipzig since its founding in 2009, about the rise from the Oberliga to the Champions League, about criticism of the Red Bull model, and also about the fact that more and more clubs have the same owner.

If there are clear rules and the integrity of the competition is not in question, Multi Club Ownership is a great opportunity because it allows for additional investments in football. And that benefits everyone in the end.

Johann Plenge

CEO RB Leipzig

That a representative of Red Bull praises the model of Multi Club Ownership practiced by the corporation is not surprising. However, it is remarkable how openly Plenge handles terms like “integrity of the competition” and calls for clear rules. To remember: Many observers accuse Red Bull of undermining exactly this integrity of the competition and circumventing the existing rules. The 50+1 rule in Germany, for example, is supposed to prevent investors from gaining too much influence. Theoretically, RB Leipzig should not even exist. But instead of theory, Plenge is only interested in practice. “What is crucial is how the one who grants the license evaluates it. And that is the DFL,” he says. “There is a clear picture. We have never had a problem with licensing in all these years.”

This is because RB Leipzig formally adheres to the 50+1 rule – and therefore does not belong to the clubs exempt from the clause. The German Football League (DFL) granted special permission to the two factory clubs VfL Wolfsburg and Bayer Leverkusen. They are allowed to participate in Bundesliga operations, even though they are controlled by Volkswagen and Bayer. TSG Hoffenheim, also belonging to SAP patron Dietmar Hopp, fell under the DFL’s exception rule for a long time but officially returned to the clubs where the 50+1 rule applies in November 2023 because the majority of votes had returned to the parent club. However, it is clear that TSG Hoffenheim would not be a significant player in German football without Hopp.

And now comes Jürgen Klopp

Hopp, Red Bull, and also Martin Kind, a confessed opponent of the 50+1 rule and a strong figure at second division club Hannover 96 for almost three decades – they have been the target of many German fans for years. Recently, someone new has joined this list, someone about whom it was previously said that all of German football could agree on him. Since January, Jürgen Klopp has been the head of Red Bull’s global football network and thus, at least in the German-speaking world, the face of investor football.

From Klopp’s time at Borussia Dortmund, the story is known that he fell asleep on a truck after a title parade, only to wake up alone and hungover in the truck garage. At FC Liverpool, people also loved him for drinking so much beer at the Champions League victory parade in 2019 that there was a fear he might fall off the bus. And now, in January 2025, Klopp sits at his presentation in a new role in a hangar at the airport in Salzburg, repeatedly sipping from a Red Bull can and saying, true to the company’s slogan, he wants to give people wings.

Klopp’s task is to improve cooperation between Red Bull’s football locations in Leipzig, Salzburg, New York, Bragantino, Paris, Leeds, and Japan. He will spend a lot of time on planes in his first weeks in office, appearing at the various branches of the Red Bull empire in the stadium. However, what exactly his job is remains vague at his presentation in Salzburg. It seems that neither he nor the corporation have a clear idea of what Klopp’s job entails. Perhaps this is logical, Klopp has just taken up his position. But for now, the impression remains that Red Bull hired the universally popular former coach mainly for image reasons, to give the controversial corporation’s involvement in football a positive spin.

In any case, for sports economist Christoph Breuer, it is clear that Klopp’s signing proves the increased importance of Red Bull in football. During the conversation in his office in Cologne, Breuer says:

The personnel decision shows that Red Bull is also attractive to people who do not need a position with the corporation for financial reasons and may fear damage to their own image. We will see if the move improves Red Bull’s image – or damages Klopp’s.

Christoph Breuer

Sports economist

And we will see what role Klopp will play in further changing football with Red Bull.

Contributors: Nils Weinert (storytelling and design), Sebastian May (storytelling), Christoph Kühne (graphics), Chantal Ranke (editing and storytelling)